The crisis is a double whammy for the US power

sector: reduced economic activity means lower sales

and dropping commodity (oil, gas and coal) prices

mean lower wholesale power prices. You combine the

two and it spells lower revenues, decreased earnings

and reduced asset valuations for unregulated (i.e.,

merchant) assets. However, it is not just the crisis that

will have an impact on the US power sector but also

the new laws, polices and regulations that will be

enacted under the Obama administration. In addition,

states will make moves of their own, continuing a

trend that started in 2005 when it became clear that

the Federal government was not going to do much

during the second mandate of President Bush.

|

|

As a result, we foresee serious impacts for both

investor-owned utilities (IOUs) and independent

power producers (IPPs). Overall, IPPs will have a

much tougher time in the next 2-3 years but they are

used to it since they just went through a terrible period

in 2002-2005; those who survive know that they will

enjoy a stronger recovery later, especially if they

develop wind projects.

Demand for electricity will drop

through at least 2010 and further demand

growth will be kept in check by increased

energy efficiency and demand management

efforts. As a consequence, many generation

projects will be delayed or cancelled and

new plant additions – beyond what is

already under way - will not be needed until

past 2015 in several regions of the country.

Greenfield project development activity can

be expected to drop by nearly half for fossil

fuel plants. It will be a whole different story

for renewable plants which will enjoy

strong support but the ones that will benefit

from it will not be for the most part your

traditional IPP players.

In the following, we try to quantify

these impacts on both utilities and IPPs

over the next seven years.

LOWER AND THEN SLOWER DEMAND

The first impact is reduced electricity

usage for the next 2-3 years – up to 350-400

billion kWh less in 2010 which is a 9% drop

(or $30 billion in sales) compared to was

what projected pre-crisis. That’s not small

potatoes: the crisis could mean a sales volume

loss of over 1,100 billion kWh through

2011 – that’s over $100 billion in revenues

less than what IOUs were counting on

when they were preparing their capital

expansion plans about a year ago.

As a result, we believe that, in spite of

the numerous rate increases that were

approved in 2007-2008, IOUs’ revenues for

2009 will be 3-4% below 2008 levels. We also

forecast that utilities’ earnings will drop by

at least 5%-8% this year. In our analysis, we

find that about one IOU out of three will

see its 2009 earnings drop by 20% or more

and almost half will see earning drops over

10%. So, we project that the amount of cash

that IOUs will get from operations will drop

by $12-18 billion in 2009 – that’s a 25-30%

cash flow reduction right there.

Longer term, we see the potential for

a more permanent reduction in electricity

use if all the investments in energy efficiency

and automated metering infrastructure

(AMI) that are currently being considered do pay off as advertised. In addition to

launching a huge weatherization effort, the

government plans to invest billions of dollars

in retrofitting existing public facilities

and has signed up with 16 energy-saving

companies to execute up to $80 billion of

energy efficiency upgrades. Likewise, the

talk about smart grids has reached hype

conditions. Nonetheless, even after trimming

by half the announcements that have

been made, it is not unreasonable to see

the penetration of AMI jump to 40-50 million

meters by 2015. How that would translate

into peak demand shedding and actual

kWh savings remains to be seen but, even

after haircuts, it may mean 30-40 GW of

additional demand-side management and 4-

5% savings in electric usage. In that case,

demand growth is then much more in the 1.1%/year range rather than the 1.4-1.6%

range we got used to recently. Over time,

this adds up.

While there will be higher-than-average

peak growth in 2011-2012, as the recovery

takes off, peak growth can be expected

to stabilize around 1.4%-1.5% in 2014-15.

Compared to what IOUs were forecasting

before the crisis, we see a system peak

drop of 30 GW in 2011and we anticipate

that drop to persist through 2015 when it

may still be around 25 GW.

LOWER WHOLESALE GENERATION PRICES

AND ASSET VALUATIONS

Decreased oil, gas and coal commodity

prices will result in lower wholesale

power prices in all organized power pool

markets. Given the correlation that exists

between natural gas prices and power

(energy) prices in most regions of the

United States, near-term pressure on gas

prices will also affect profits from coal

and/or nuclear merchant plants. In addition,

a slowing economy and energy efficiency

also threaten to reduce power

demand growth below levels we might have

previously looked for.

Compared to their 2008 levels, expected

prices for 2009 will drop by 15-40%

depending on the type of power, baseload,

around the clock (ATC) or peaking. On

average, the drop is about 25-20%.

Longer term, wholesale power prices

will recover over a 2-3 year period as commodity

prices increase again and power

demand recovers. Prices for 2010 may

recover somewhat (say, by 5%) but it will

not be until 2011 that prices will get back to

their 2007 level and they may not recover

their 2008 level until 2013 at best. So, for

the next 5 years, the industry will basically

experience deflated prices; the average

price through 2013 is estimated at 85% of

2008 prices. Past 2013, prices will be

impacted by Federal carbon policy if a new

GHG bill has been passed.

These wholesale price trends imply

lower merchant asset values with a drop on

average of 35-40% over last year (mid-2008).

Coal plants using Eastern coal may show

the worst drop, followed by load-following

gas-fired units and then nuclear and wind.

These fuel-specific asset changes will

impact over half of the IPP asset base,

including the larger players, even those

with hedged and relatively well diversified

asset portfolios. This has been reflected in

the recent stock price drops of several publicly-

owned IPPs. Many IPPs will have to deleverage and sell assets; some of the top

10-15 IPPs may actually be bought out. This

will result in some industry consolidation

and possibly as much as 30-40 GW of secondary

market transactions in the next two

years.

REDUCED PLANT ADDITIONS

When we factor all these efforts, we

see delays of two years or more in the need

for new plants. In many regions, the need

year (i.e., when new plants are needed to maintain the proper reserve margin in that

area) has been pushed back to 2015-2017.

Given the amount of current backlog that is

still expected to proceed (some with

delays) in spite of the crisis, only a few

regions really need plant additions by 2014.

This means that IPPs will not have much

project development work to carry out for a

while.

We estimate plant additions to drop

by 35 GW between 2009 and 2015, compared

to what was planned in the summer

of 2008 before the crisis hit. The biggest

impact is on fossil plant additions: 12 GW

less for new coal capacity and 26 GW less

in new gas plants for a total of $55 billion in

reduced capital commitments over the next

seven years. The only bright spot is that

renewable plant additions will do better

thanks to the new tax incentives and

monies provided under the Obama administration.

We now project total capacity additions

in the US power sector of roughly 80-

85 GW through 2015 – including 18 GW

(21%) of coal; 28 GW (33%) of gas; and 38

GW (46%) of wind. About 30-35 GW

remains in development play, mostly in

wind projects.

|

Furthermore, the bulk of new IPP

additions being in wind, much of the new IPP development activity will involve a new

crowd of players. This will be a big change

for traditional IPPs that mostly focused on

gas or, for some brave ones, coal plant

development. Many IPPs – including the

largest publicly-owned IPPs - will put on ice

most of their greenfield opportunities or

focus on “backyard project development”

by expanding or repowering their own

plants or focusing on a few regions rather

than trying to expand nationwide.

PROSPECTS FOR WIND

Renewable energy – including wind,

biomass and solar – will do better. IOUs

and IPPs are chasing all three and there are

already over 80 GW of projects under consideration.

In the following, we focus on

wind.

About 8.4 GW of new wind plants

came on line in 2008; this brought the total

amount of wind capacity in operation at the

end of 2008 at 25 GW. Wind provided 35%

of power plant additions in both 2007 and

2008 so it has become a major energy

source.

There is another 4.5 GW under construction

most likely to come on line in 2009-2010 and the current wind project

backlog is huge, up to 74 GW consisting of

over 400 projects. This mpressive backlog

is also the result of 2-3 years of very active

development pursued by over 100 companies

that were counting on the continuation

of a strong tax incentives and significant

participation from a growing number of

financial investors. If we extrapolate the

industry’s project development track record

to date, only a third of the backlog capacity

will get built – that’s still 25 GW. However,

we also need to look at the market drivers

and constraints that are likely to impact the

wind project development activity over the

next 5-7 years.

On one hand, we have a very strong

policy support for wind. The 2009 Stimulus

bill (ARRA) provides developers with a

choice between three tax incentives for projects

developed through 2012: a $21/MWh

production tax credit (PTC); or a 30%

investment tax credit or a cash grant in lieu

of an ITC. So, wind project developers now

have access to a broader range of incentives

which can now be tapped for a longer period, until the end of 2012. This 3-year 3-

incentive environment provides more visibility

than the industry has been able to

plan on in the past 5 years.

Another possible positive development

for wind would be the passage of a

Federal RPS standard in the next 12-18

months followed by the possible implementation

of a new cap-and-trade greenhouse

gas (GHG) regime that could be in place in

2013-2015 and would further foster the

development of wind projects. A Federal

20%-25% RPS could create a 20 GW or so

boost by 2015 in demand compared to a

state-mandated-RPS only scenario. That

boost would not materialize over night but

would be noticeable by 2013-14 and developers

may choose to anticipate it by 1-2

years. If they do, that means a resurgence

of development activity by 2011. However,

opposition to an RPS will be strong; furthermore,

there is a growing probability that

the Federal RPS be rolled into a new GHG

law.

The implementation of a cap-and-trade

GHG regime would further boost the

demand for renewables for the post-2015

period. Carbon prices in the $15-30/ton

range, quite possible for the 2015-2020 period,

could in theory imply an extra $5-

10/MWh bonus for wind projects. However,

once a cap-and-trade system is in place,

some if not all of the tax incentives that

have been made available for wind would

supposedly lapse. It is difficult to estimate

how this will affect prevailing wind prices in

2012-2105 when that mixed transition to

Federal RPS and then to cap-and-trade is

likely to take place, but it is reasonable to

assume that wind prices could benefit from

a $5-10/MWh boost for a while.

On the other hand, there are four market constraints that will affect future

wind project development prospects:

• How efficiently can developers use

available tax incentives

• An expected softness in negotiable

wind prices for the next 2-3 years

• Delays in RPS requirements due to

crisis-induced reductions in

electricity demand

• The need for new transmission

investments to enable the

development of more wind

resources.

Given the crisis and the low level of

profits that are being made, both PTCs and

ITCs have limited value to project developers.

Worse, these developers now cannot

find many financial institutions to whom to

sell these tax credits; the number of such

institutions has dropped from over 20 in

2007-2008 to less than 4 in the past five

months and their funding appetite has

dropped from $4 billion to half that at best.

This is now a one-year problem and it may

take 3 years for the situation to turn

around. In that context, the cash grant

incentive looks the best but it is a new incentive for which DOE needs to define

the rules and that may mean some delays.

Meanwhile, power prices for wind will

suffer the way wholesale power prices will,

so there will be further softness in the next

two years. Furthermore, a weaker power

demand will delay the timing and size of

many utilities’ RPS requirements by possibly

as much as 25 billion kWh in 2015; this

in turn would reduce by 7.5 GW the

amount of wind required by then – or the

equivalent of roughly 1 GW/year over the next seven years.

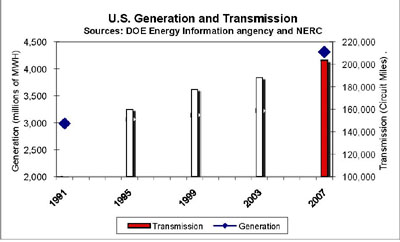

Finally, many wind projects cannot

proceed unless more transmission lines are

built. This is not a new issue and many utilities

have proposed new lines. However, the

track record for approving new lines is iffy.

In addition, there are competing demands

for capital since there are over a dozen

high-priority transmission expansion projects

(requiring over $15 billion of investments)

already under consideration under

DOE’s National Transmission Corridor initiatives (NIETC) launched in 2005. How

that affects the prospects for the other 30

potential transmission projects that could

spur the development of another 40-50 GW

of wind resources remains to be seen, especially

since these wind-related projects

could require over $25 billion of investments.

Together, that means $40 billion of

spending for an industry that was already

maxed out when it invested about $7-8 billion

in transmission per year in 2007 and

2008. |